Why Did "The Ocean is Broken" Go Viral?

In late October, we saw a big, sustained spike in online attention to an article that came out in the Newcastle Herald, entitled “The Ocean is Broken.” The story chronicles ocean yachtsman Ivan Macfadyen’s experience retracing a trans-ocean journey he had sailed 10 years ago, and his shock at the profound decline he saw in sea life and ocean health. According to the Herald, the article “smashed Fairfax Regional Media records.” The article, definitively lacking hard science, clearly struck a chord with readers worldwide, and Macfadyen is now fielding requests for interviews, letters from concerned citizens, and offers from documentary filmmakers to help tell his story.

Our community of ocean lovers and ocean communicators was intrigued, so we decided to don our Upwell analysis hats and put our Big Listening tools to the test, to answer a couple key questions. First: Why did this story, above all the others that talk about ocean health, go so big? And second: What can Team Ocean learn and apply to our work?

The Numbers

"The Ocean is Broken" has been shared over 115,000 times on Facebook and Twitter, and is still being shared now, a month after it was originally published. In fact, in just the last week, the story has been shared between 40-80 times per day.

The story was first shared midday in the UK on October 18 (early am in the US), but didn’t achieve real momentum until it was shared by Caitlin Moran on Twitter on October 20. The British media personality and author has 470,000 followers on Twitter, and is known for her humorous (and often NSFW) tweets and her high level of engagement with her followers.

Several other Twitter "celebrities," including Twitter founder Jack Dorsey, shared the story but it seems this tweet was what tipped the initial scales.

The story did exceptionally well on Facebook, with over 100,000 shares, nearly 100,000 comments, and over 85,000 likes, heavily overshadowing numbers on Twitter. (Source: SharedCount)

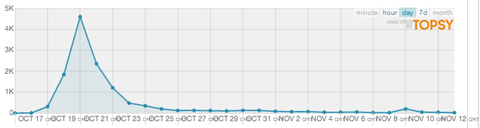

The shape of the “spike” is much wider than similar stories would be. This means there was sustained volume over several days, and the story had legs for much longer than 24 hours. Indeed, Twitter conversation levels in the past week have remained in the 40-80 mentions per day level. (Source: Topsy Pro)

A story with real legs: Twitter mentions of “The Ocean is Broken” Oct 17-Nov 13.

It's a human interest story.

The data above tell only part of the story. The heart of the story lies in understanding why the initial people who read "The Ocean is Broken" decided to proactively share it with their friends, followers, readers and fans. With articles coming out every week that tell us oceans are hurting, why did this one go viral?

One thing that's important to distinguish is that this is not a science story, or an environmental story. It is a human interest story. The author, Greg Ray, was not writing an article about ocean health. He was recounting and sharing the powerful personal anecdotes of Ian Macfadyen.

When we, as conservationists and scientists, want to connect people to an issue we find important, such storytelling is a powerful tool. A story can bring a wonky issue to life. Take, for instance, the health care reform law (Obamacare). Journalists, nonprofit organizations, and government agencies are relying on storytelling to connect with people. A story about how someone who had been previously denied health coverage due to a pre-existing condition is much more interesting than an article detailing all the changes in the new law.

Scientists are often trained out of including narrative or anecdotes in their writing, but this is a reminder that that reluctance to get personal can come with a cost.

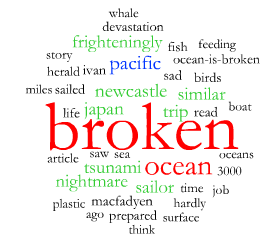

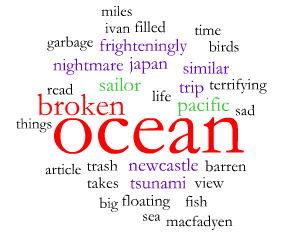

Not only did "The Ocean is Broken" tell a story, it was able to incite emotion. With Radian6, we were able to get a better understanding of people's reactions to the article, en masse. The below three word clouds represent the three days that saw the highest volume of sharing.

Note that the emotive words are closely related: nightmare, frighteningly, terrifying, disturbing. With lower frequency we see words like sad and depressing. While positive emotions tend to spur social sharing at a higher rate than negative emotions overall, it is also the higher energy emotions that spur sharing. Fear is a higher energy emotion than sadness. The language used in the article, from the very beginning paragraphs, is clearly meant to evoke these nightmarish fears:

The wind still whipped the sails and whistled in the rigging. The waves still sloshed against the fibreglass hull.And there were plenty of other noises: muffled thuds and bumps and scrapes as the boat knocked against pieces of debris.

The article is also written for the web: short paragraphs that make scanning easy, a powerful and personal banner image to catch the reader's attention, and a confident and potentially controversial title that makes the reader want to learn more. "Broken" isn't a word we're used to hearing in the context of the ocean - it's poetic, symbolic, and new to our lexicon. And if someone saw the phrase "the ocean is broken" in a tweet, there's a good chance they might have hit Retweet without even reading the article because they agreed with the headline so strongly (admit it: you've done the same thing.).

There's certainly more to learn from this story - tell us your thoughts in the comments.

Add a comment