Equally Evil = Socially Awesome: Unpacking The ICRS 2012 Spike

Update: A Look At The Ensuing Conversation

On July 13th, the New York Times posted an Op/Ed by Roger Bradbury, an ecologist at the Australian National University. Entitled "A World Without Coral Reefs", Bradbury advanced the view that a total collapse of coral reefs was all but certain, and proposed that we should reallocate funding to account for this reality. In his words:

They have become zombie ecosystems, neither dead nor truly alive in any functional sense, and on a trajectory to collapse within a human generation. [...] But by persisting in the false belief that coral reefs have a future, we grossly misallocate the funds needed to cope with the fallout from their collapse. Money isn’t spent to study what to do after the reefs are gone — on what sort of ecosystems will replace coral reefs and what opportunities there will be to nudge these into providing people with food and other useful ecosystem products and services.

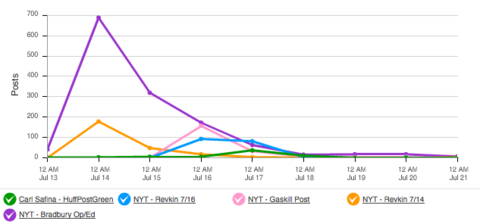

With its alarming title and controversial assertions Bradbury's editorial immediately received a burst of mentions online. The New York Times doesn't enable commenting on its Op/Ed posts, so the discussion of this post took place largely in social media, as you can see below:

Several noted science and conservation journalists were quick to respond, including The New York Times' Andy Revkin ("Reefs in the Anthropocene – Zombie Ecology?" and "More on Coral Reefs and Resilience or Ruination"), Melissa Gaskill ("When Coral Reefs Recover"), and Carl Safina ("Life Finds a Way -- But Needs Our Help"). These posts each received their share of online attention, though none approached the number of mentions of the Bradbury post.

However, since these responses were made as comment-enabled blog posts, a good portion of the resulting engagement took place in the comments. This was especially true for Andy Revkin's two posts, which have (as of July 24th, 2012) received 79 and 43 comments respectively. This is likely attributable, at least in part, to Mr. Revkin's active use of social media sites such as Twitter, where he has over 37,000 followers.

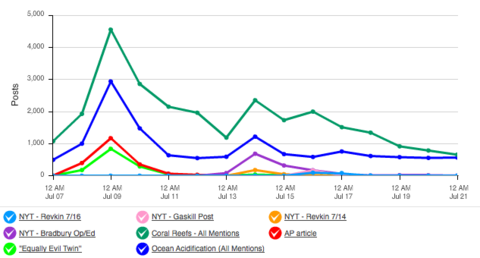

To better place the post-ICRS conversation in context, here's what it looked like relative to ICRS itself, and the accompanying bump in online mentions for both coral reefs and ocean acidification that ICRS generated:

Between July 13th and 20th, the "World Without Coral Reefs" Op/Ed received 1,384 mentions. This is nearly exactly as many as Jane Lubchenco's "equally evil twin" quote received the week before (1,398), and a useful illustration of the "social liquidity" of emotional content. As is often the case, controversy moves faster than context, even online.

[Update concludes here. What follows is the original ICRS unpacking post.]

ICRS - The Big Picture

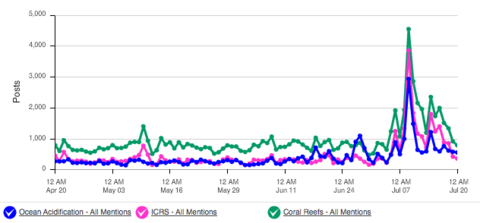

The 12th International Coral Reef Symposium took place earlier this month. Coral reefs and ocean acidification were two of very first ocean conversations that we began monitoring here at Upwell, so we were understandably interested to see what impact, if any, ICRS would have on these topics.

What we found was both encouraging and informative, and we’d like to share it with you.

ICRS was responsible for the single largest spike in online mentions of both ocean acidification and coral reefs in 2012 (thus far). For example, ocean acidification typically receives between 200-300 posts per day. But on July 9th, the first day of ICRS 2012, ocean acidification was mentioned nearly 3,000 times.

The impact of such large bumps in attention can not be overstated, especially for a topic like ocean acidification, which has yet to firmly establish itself as part of the mainstream dialog. (At least not in the way that say, climate change has.) By boosting their profile beyond small, core groups of scientists and activists, these conversations can reach the new audiences that are crucial for raising the ongoing baseline. That ICRS was able to generate such a marked increase in both the coral reef and OA conversations is a laudable accomplishment, and a promising sign for the future.

Unpacking The Spike

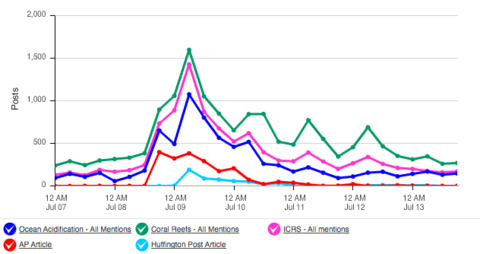

What generated this burst of attention? By far, the bulk of the online attention surrounding ICRS 2012 was the result of a single event: NOAA Undersecretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere Jane Lubchenco’s plenary address, and the resulting Associated Press article, “Science official: Ocean acidity major reef threat”. This story was quickly picked up by many other news outlets, including USA Today and the Huffington Post, and was widely tweeted about and shared online.

Equally Evil = Socially Awesome

The popularity of this article also illustrates the power of succinct, impactful messaging. In her address, Lubchenco vividly described ocean acidification as “climate change’s equally evil twin”.

Effectively bridging the gap between science and emotion, such statements are ideal for social media, where the decision to share content is made in seconds, driven as much (or more) by the heart than by the head. We can see this effect particularly well in the following comparison.

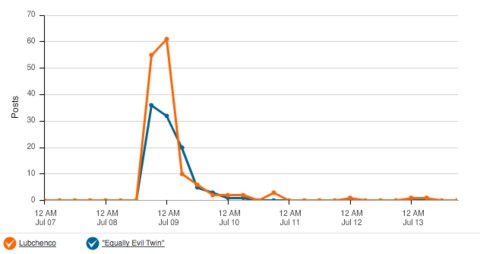

The first graph shows online mentions of both Jane Lubchenco (orange line) and her “equally evil twin” quote (blue line) from news media outlets only. During ICRS, Lubchenco received 144 mentions in news media online. In comparison, her quotation was mentioned only 98 times.

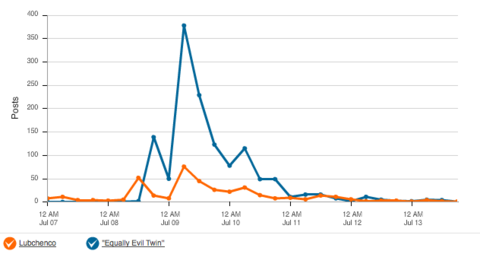

Turning to social media however, this relationship becomes completely inverted. During the week of ICRS, the “equally evil twin” quote received 1,298 mentions in social media, while Jane Lubcheno was mentioned by name only 394 times.

This is a vivid reminder of people’s inclination to care more about the sentiment of a quote than the accuracy of its source. At least when it comes to their initial decision to share content online.

Certainly attribution and context are important, but online, where such deeper knowledge is only a click away, the more easily people can communicate the heart of a story—the essence of why this is important and you should care about it—the more likely that story is to be shared. By intentionally providing them with such handles you drastically increase the likelihood that your content will receive the widest possible attention.

Don’t be shallow. Don’t resort to exaggeration or baseless hyperbole. And certainly don’t lie. Rather, simply remember that the river of online news is endlessly asking people to understand, to care, and to act. (Even if that ask is “merely” a share, or a Facebook like.) The easier and faster you can make that process, the more liquid your content becomes. Encapsulating a difficult issue like ocean acidification as effectively as Jane Lubchenco did at ICRS is an excellent example of doing this right.

Add a comment